Transforming How High School Is Taught Is Tough, But Possible: How I Did It

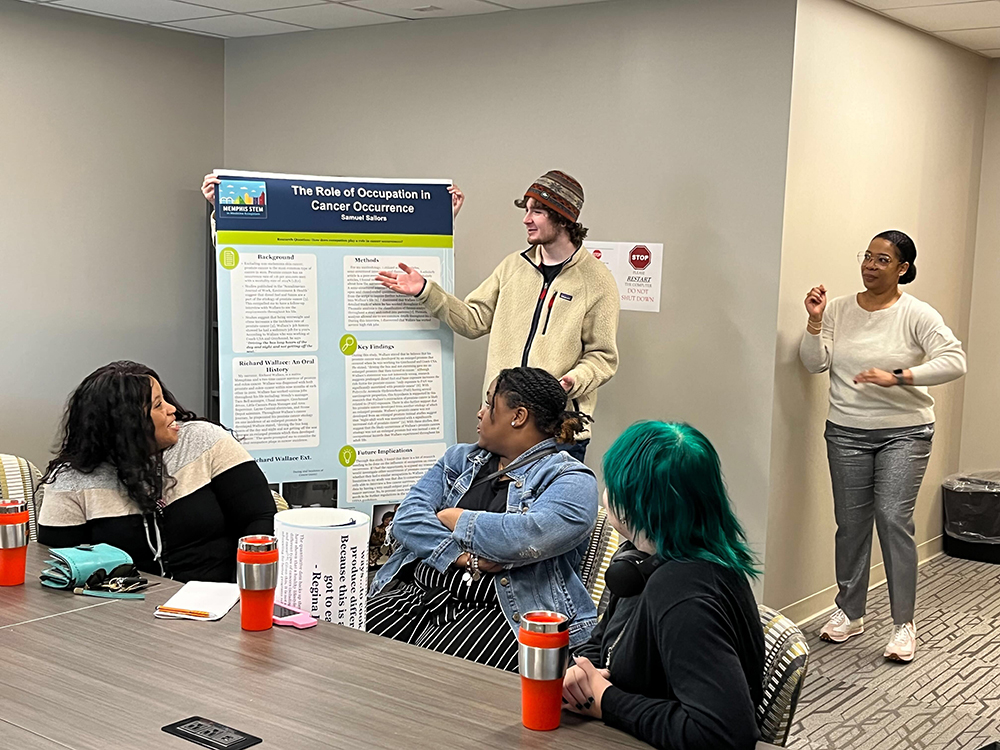

This story was produced by The 74, a non-profit, independent news organization focused on education in America.My life as a teacher is dramatically different now than it was five years ago. In my current Memphis high school biology classroom, students are caught in a whirlwind of activity, exchanging ideas and vigorously documenting observations. They’re immersed in an experiment analyzing pollution in local soil and its correlation to cancer rates, an all-too-real issue in our community. These are the moments that affirm my decision to become a teacher. They are also the moments that make me grateful to still be in the profession and grateful for the path that brought me here.Sadly, I know this experience is not typical; not every school generates the conditions that inspire and support educators to design transformative learning experiences for their students. But if we’re going to protect the teaching profession, we need every school to understand what teachers value — and meet those needs — because that’s also the best way to serve students.Before joining Crosstown High in 2018, I felt frustrated after eight years teaching. I had taught at several different schools in Memphis and did my best to make science as engaging as possible. But my previous schools were part of a rigid system that didn’t allow for the flexibility to meet students’ needs or the freedom and resources to make learning relevant to the real world. I saw many of my students struggle to stay engaged, and I knew that even when they graduated with good grades, they weren’t leaving high school prepared for college and careers.Even worse, it seemed like having high expectations for my students and providing learning experiences that allowed them to dream big wasn’t enough to overcome a system that was quick to stamp out those dreams. In one school, I had a brilliant student in my Advanced Placement biology class who understood protein folding — a particularly difficult topic — and we were on a roll. But one day I looked up and she was no longer in class. I found out she got expelled for smoking weed. She never even graduated from high school. We were harming children with this rigid system. Educators wanted more for our students, but we did not have room to grow, to try new things, or access outside resources.When I learned about Crosstown High, I sensed that this might be a place where I could rediscover my passion for teaching. It promised personalized courses of study and hands-on work within the community. The school’s founders also created it to be diverse by design, unlike most Memphis high schools, which remain highly segregated by race. I took the leap and joined as a high school biology teacher when it opened in the fall of 2018.I can’t pretend that moving to Crosstown from a school that did things the way they’ve always been done was easy — for me or for my students. Crosstown’s approach to education is very different from what any of us were used to. Students learn through doing; they can spend a whole semester working on a project that combines math and science, or English and humanities. They still have to meet state standards but learning feels more relevant. Through the school’s partnership with XQ, everything is focused on a set of Learner Outcomes that are designed to ensure students thrive in their lives beyond high school. These include mastering fundamental literacies — a solid academic core — and being an original thinker for an uncertain world.

With these outcomes in mind, I planned a project that I was convinced would excite and engage my students, an exploration of “Life on Mars“ to teach core biology concepts. They experimented with plants to determine which ones could produce oxygen on the planet. Students also explored the types of protections needed to preserve life on Mars and for travel through space. They made new connections to ecological succession — the process in which plants replace or succeed each other over time — and saw how these trends on Earth could inform a process for creating a “Green Mars.”But it did not go as planned. No matter how engaging the activities were, my students didn’t get the point of spending their time this way. Some didn’t feel like they were learning and wanted what they called “regular work.” Accustomed to memorization and regurgitation, it can be jarring for students to jump into cross-curricular projects that require peer collaboration and real-world applications of concepts. I was frustrated, too, and almost gave up on this new way of reaching my students.But, I decided to prove to my students and to myself that this method could be both relevant and rigorous. Ten weeks into the school year, I gave the most skeptical group of students a version of the state’s standardized end-of-year science test. I selected about 40 of the questions relevant to the topics covered in the Mars project, and these students scored an average of 90%. They were surprised and overjoyed. They saw how at the same time they were collaborating with each other on projects that demanded their use of critical thinking skills, they were also mastering the core competencies they would need for success in college. After this moment, there was no going back to the old way of doing things. But my challenge didn’t end there.

Every educator knows what it feels like to try to make magic happen on your own. We do our best to modify curriculum, design engaging learning experiences and gather the resources our students need. But it’s incredibly difficult work. And when you’re designing project-based learning experiences like what we do at Crosstown, I found myself needing extra support after that challenging first year. Here’s what I learned:Look for help — find community partners. Thankfully, I wasn’t alone. I was encouraged to partner with experts outside of my classroom and to bring resources back to my students. The summer after my first year at the school, a group of researchers from local universities and research centers approached Crosstown for help in designing a 9-12 curriculum called “Cancer Learning In My Backyard.” As I worked with their doctors, I felt my expertise as an educator was truly valued. I knew the curriculum we were designing together would have an impact on my students and make a difference in the world far beyond my classroom.Representation and community matter. Having the time and support to work with these local researchers allowed me to continue to design projects while transforming my perspective on teaching. Many of these researchers were women of color in fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics, which also opened students’ eyes to aspirations for their futures. Since then, I’ve continued to bring researchers to my science classes and I’m now teaching a different version of “Life on Mars,” which evolved with the community partners.Innovation and the support to “fail forward” are key to student success. We become educators to see our students succeed, to help our communities thrive and to make a positive impact in the world. Crosstown’s collaborative approach affirmed my belief that teachers don’t need to be burned out, and students don’t need to be bored. It’s critical to give teachers the autonomy to design learning experiences to engage students and create meaningful connections to their community. This can also help schools retain Black teachers like myself by making us feel valued as professionals.Core academics and real-world relevance are vital for success. The schools where students buzz with interest and where educators are fulfilled by their work are also the schools where students thrive academically. In 2022, 95% of Crosstown’s first cohort graduated on time, a higher rate than that of the surrounding district and the state of Tennessee. Our students got better results on several standardized tests — such as the ACT’s college-ready benchmark in English — than their local, statewide and national counterparts. We also had stronger results across the board with students from low-income families and students of color, which is important for a school that aimed to be “diverse by design.”

I’ve learned through Crosstown that high school transformation is possible when educators are part of a larger community of experts, and when the school commits to designing learning experiences that are both relevant and rigorous. It’s not always easy. Teachers often feel like they have to have every minute of the day planned out. But real learning requires us to let go. I don’t have all the answers and that’s OK. Students should know we’re always learning, always researching, always asking questions. Because that’s the best model for a successful life.