All Teacher Shortages Are Local, New Research Finds

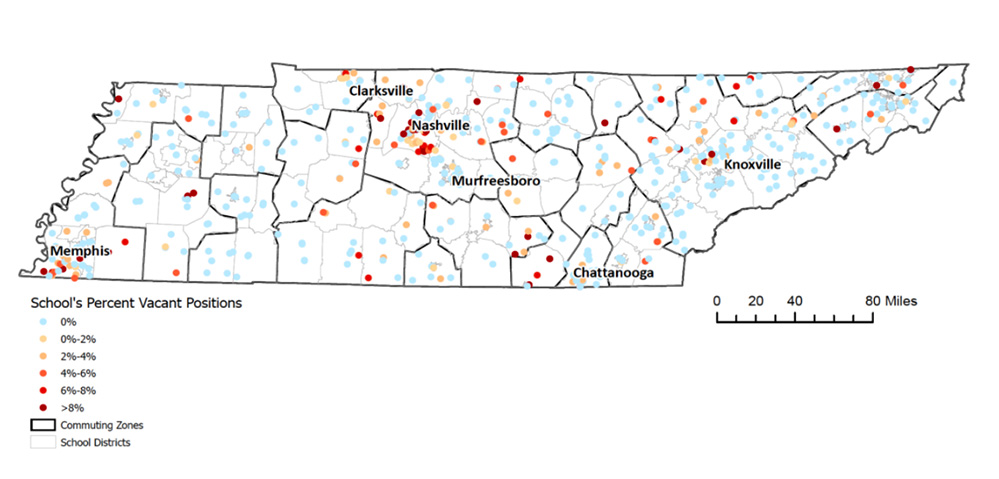

This story was produced by The 74, a non-profit, independent news organization focused on education in America.K-12 teacher shortages — one of the most disputed questions in education policy today — are an undeniable reality in some communities, a newly released study indicates. But they are also a hyper-local phenomenon, the authors write, with fully staffed schools existing in close proximity to those that struggle to hire and retain teachers.The paper, circulated Thursday through Brown University’s Annenberg Institute for School Reform, uses a combination of survey responses and statewide administrative records from Tennessee to create a framework for identifying how and where teacher shortages emerge.Those data principally come from school years leading up to 2019–20, anchoring the results in the pre-COVID era. But they will inevitably resound in debates over the pandemic’s effects on the education workforce, which have come to revolve around the central paradox of teacher shortages: Even as countless school and district officials say they’re struggling to fill positions, national labor statistics show only slight movement in teacher turnover rates the last few years.Matthew Kraft, a Brown economist and one of the paper’s authors, said that ambiguity around shortages arises from the decentralized nature of K-12 employment, which can bely the realities experienced by many teachers and administrators.“Teacher shortages are real, period,” Kraft said. “Teacher shortages, however, are not universal. We’re trying to help people understand that it’s actually accurate for people to disagree about this because they’re answering from different perspectives.”To conduct a comprehensive examination of K-12 employment, Kraft and his collaborators gathered response data from the Tennessee Educator Survey, an annual poll administered to thousands of teachers and school administrators by the state department of education. Tennessee offers a fairly representative setting, including several major urban districts along with substantial suburban and rural populations.Specifically, the study leveraged a survey item asking administrators if their school had a vacant teaching position at the beginning of the 2019–20 school year. Respondents at roughly 1,100 of Tennessee’s 1,740 schools answered that question, which provides a reasonable proxy for teacher shortages; while virtually all schools occasionally have to deal with unfilled jobs, classrooms that begin the academic year with insufficient or uncertain staffing may struggle to accelerate learning and establish relationships between students and teachers.The responses, along with a decade’s worth of state information on student and teacher demographics, paint a picture of shortages that are both widely distributed throughout the state and narrowly experienced among schools themselves. To begin with, just 609 of the sample’s more than 40,000 teaching positions were vacant in the fall of 2019, with secondary schools accounting for 73 percent of all vacancies. But while three-quarters of all schools reported no vacancies, and just 6 percent of schools said that more than two positions were vacant, schools in virtually all of Tennessee’s commuting zones — common units measuring discrete economic areas — reported at least one teaching vacancy.

Secondary schools in a handful of areas, including Memphis and Nashville, stand out as sites of acute shortage, but vacancies were seen throughout Tennessee rather than concentrating within specific regions or counties. About 80 percent of the variation in vacancy levels, in fact, was accounted for by particular schools within districts, rather than across school district borders.What’s more, the existence of vacant positions was significantly associated with certain features of schools and school communities. In keeping with earlier research showing that K-12 teachers — to a greater degree than other professionals with a similar level of educational attainment — prefer to find jobs near where they grew up, the authors discovered that schools employing a higher proportion of early-career educators who themselves attended a nearby high school (another question included on the statewide survey) reported fewer vacancies.Teacher compensation also played an important role. A 0.5 percentage point increase in teachers’ scheduled salary bumps was correlated with a 36 percent drop in vacancy rates, while increases in a combined measure of self-reported working conditions (e.g., better school culture, more administrative support, strong relationships among faculty members) also drove down teaching shortfalls at the beginning of the year.But perhaps the strongest indicators of unfilled teaching jobs were school-level turnover rates. This result may seem intuitive — more vacancies are naturally seen in workplaces where more people regularly leave — but Kraft and his colleagues highlight the finding as a validation of earlier work on “revolving-door” schools; for state and district leaders hoping to identify and support schools that struggle to staff classrooms, it is an important observation that past turnover tends to predict future turnover, especially when real-time data on teacher quit rates are typically hard to come by. In all, turnover rates were found to be 39 percent higher in schools with fall teacher vacancies than those without.“For 20 years, we’ve been seeing that revolving doors predict shortages,” observed coauthor Danielle Edwards, a postdoctoral research associate at the Annenberg Institute. “There’s something important about that measure, [which] doesn’t include the past year’s turnover. It’s the idea that a particular school might always be losing teachers, and we need to identify those schools because it’s also going to make it hard for them to get teachers in the future.”Certain academic specialties are also harder to find than others. While about 20 percent of school districts said they didn’t receive enough applications for open social studies positions, nearly two-thirds reported insufficient interest in math, science, foreign language, and special education roles. That unevenness suggests that standard salary schedules may be “ill-equipped to address the wide variability in…subject-specific needs,” Kraft said.

He concluded by arguing that the frequency with which teaching jobs sit open across different communities, and the commonalities between schools that see higher vacancy levels, shows that teacher shortages both before and after COVID are the downstream effect of policies that can be altered — whether by differentiating teacher pay to attract applicants with especially valuable expertise, or improving working conditions so that all school employees feel more valued.“Shortages don’t just appear out of nowhere by some miraculous force; they are a function of decisions we make, and they can be influenced by macroeconomic patterns…like a global pandemic. But underlying them is an infrastructure that we’ve designed and have agency to change.”